King Henry IV: Part I, Act V

FALSTAFF: Can honor set to a leg? No. Or an arm? No. Or take away the grief of a wound? No. Honor hath no skill in surgery then? No. What is honor? A word. What is that word honor then? Air – a trim reckoning! Who hath it? He that died a Wednesday. Doth he feel it? No. Doth he hear it? No. ‘Tis insensible then? Yea, to the dead. But will it not live with the living? No. Why? Detraction will not suffer it. Therefore I’ll none of it. Honor is a mere scutcheon – and so ends my catechism.

On the heels of finishing Act IV, I couldn’t wait to begin Act V. One way or the other, the play was hurtling toward a dramatic climax. Either Prince Hal would clash with Hotspur in an epic duel, or somehow convert him over to the royal side.

Not knowing the actual historical events (not that this seemed to bother Shakespeare), I found myself rooting for a Hollywood-like ending, a conversion scene where Hotspur is won over to become Hal’s partner in crime. With Robin as his sidekick, together they could clean up Gotham and take a bite out of crime. Surely Shakespeare had to realize that Hotspur was his best character in the story. What writer wouldn’t be loathe to kill that guy off and let him go?

Breaking: I’m a romantic. But I don’t think I’m that far off, at least in my sense that Shakespeare was reluctant to see Hotspur leave the play. We have reason to believe from Worcester’s treachery that – if Hotspur knew the truth – he would most likely have surrendered. This turn of events thoroughly angered me (yes, I get wrapped up in these things). King Henry goes the extra mile to offer the rebels a way out of their predicament: state their claims, and he will address them and offer a full pardon to all involved. In addition, Prince Hal volunteers to grapple with Hotspur against the longshot odds in one-on-one combat. He is determined to win back favor in his father’s eyes come what may.

Unfortunately, Hotspur is not present to hear either the conditions for pardon or the terms of Ultimate Fighting against his shadow nemesis. We are virtually certain he would accept the latter in a heartbeat – he has been looking for a way at Hal since the start of the play. But as for the former, we have only Worcester’s deceit to understand that Hotspur may have taken the gentleman’s way out.

So instead of recapitulating the king’s words and allowing Hotspur to decide, Worcester deliberately lies to stoke Hotspur’s outrage and engage him in the battle. And why does Worcester do this? Because he’s convinced that Hotspur would be forgiven for his youth, valor and reputation for rashness, while the rest of the rebels would never fully be trusted again. The king, he is sure, would only look for a convenient excuse later on to get them all back.

This argument has logic, but absolutely no moral grounds other than self-survival. Therefore, it should come as no surprise that Worcester, in fact, gets his in the end. Rounded up by the king’s men, he is summarily sentenced to death. No honor, no valor, no glory to accompany his decision. If, as Isaac Asimov says, Worcester was the “brains” of the operation, then the plan was doomed to failure from the beginning. There was never a team here but a collection of self-interested individuals.

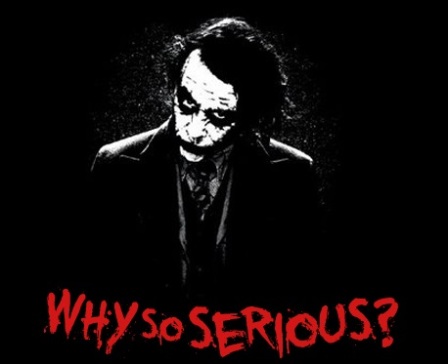

I am most intrigued, however, by Asimov’s suggestion that Hotspur and Falstaff represent polar opposites on the spectrum of the future Henry V’s personality traits – characteristics that must be reconciled for him to ascend to greatness. As much as I hate to see Hotspur die, we comprehend in graphic terms how important it is that Hal adopt a more humble approach to honor. Honor, in the ancient and medieval sense which means acquired glory from battle. It stems back to the Greeks when such heroes as Achilles and Hector fought fearlessly – not for the tactical advantages or team-building, but rather for reputations that would survive them as a legacy (the riches, fame and women weren’t bad either).

Here, then, it becomes crucial to study the contrast between Falstaff and Hotspur, and how Hal manages to reconcile and transcend them both. After killing Hotspur, he does not boast of the accomplishment, but allows Falstaff to make the claim if he can. It doesn’t say a lot for Falstaff that he would try.

As Hotspur dies, he cares less about the mortal life fleeing his body than for the honor that will now pass from him to the prince who defeated him. In his eyes, honor is a zero-sum game. Nothing he ever achieved in his lifetime will matter. You are only as notable as your final triumph or defeat. Sigh.

Thus, we close Part One with the death of Hotspur and the rout of the rebel force. Because the attack was launched prematurely, before the full storm of opposition had gathered its strength, there are still opposition armies out in England that need to be dealt with. But now, with Hal on the ascendant, Douglas captured and converted, and even Hal’s little brother John finding his mettle in the field, there seems little doubt that Henry will seize back the initiative and his reign will regain its footing.

But that remains to be seen in Part II.